Why Veedon Fleece is Van Morrison’s masterpiece

How Van escaped divorce, civil war and hippie burnout to make a classic

“Mood music for mature hippies.”

So, wrote Jim Miller in Rolling Stone’s January 1975 review of Veedon Fleece. Indeed, the hippies had matured since 1967: the Summer of Love when Van’s “Brown Eyed Girl” played on repeat.

By 1975, divorce had replaced revolution in the cultural zeitgeist, and bad trips dominated end-of-year lists. In the Village Voice’s “Pazz & Jop” critics poll, Neil Young’s Zuma jostled with Bob Dylan’s Blood on The Tracks, each detailing breakups with Carrie Snodgress and Sara Lownds respectively. While Young’s other album of 1975, Tonight’s The Night – a wasted trek into the abyss of addiction, depression and disillusionment – reached number five.

The decade that gave us the unadorned realism of Joni Mitchell’s Blue in 1971, and Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors in 1977, feels in retrospect as it did at the time: a million miles away from the euphoric idealism of the 1960s.

Van Morrison’s career followed a similar path towards alienation. In short: he quit Belfast pop group Them in 1966 and moved to America, recording “Brown Eyed Girl” in 1967. It became a smash hit, leading Van to instantly dislike both fame and pop music.

After getting into trouble with New York gangsters for refusing to write a follow-up hit, Van quit his record deal and went into hiding in Boston. Here he made the biggest left turn in pop music history, recording Astral Weeks in 1968 – a psychosexual jazz-folk odyssey, cut with Charles Mingus’s backing band. It failed to chart.

(For the best review of Astral Weeks, see Greil Marcus: “You can hear these moments of invention and gasping for air, and you reach your hand and you close your fist and when you open your fist there's a butterfly in it.”)

Van restored his career with soft rock album Moondance, in 1970, and spent the next years living in hippie idylls, Woodstock and San Francisco, with his astrologer wife Janet Planet.

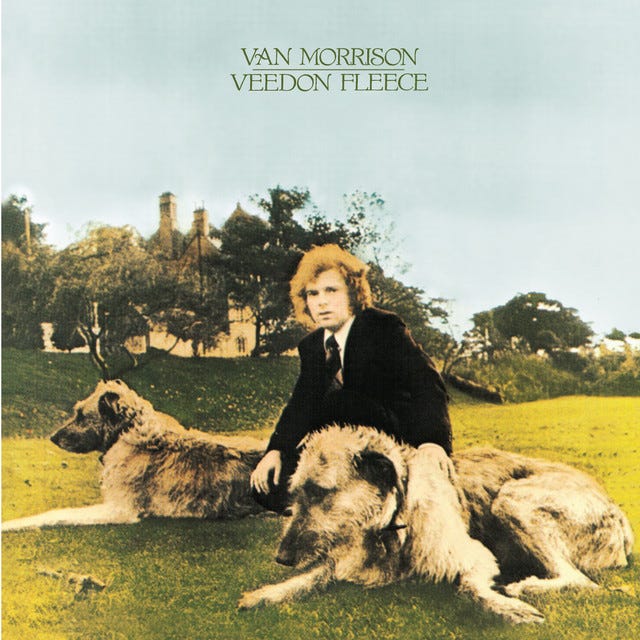

But as with Dylan and Young, domestic bliss was not in the tea leaves. The couple divorced in 1973 and Van escaped into exile, as he’d done in 1968. This time to rural Ireland, where he wrote almost all the songs on Veedon Fleece in a three-week burst. Presumably sat atop a hill with two Irish wolfhounds, as depicted on the album’s cover.

Musically, the record is a return to the Celtic folk-jazz of Astral Weeks, but it’s less focused. Where Astral Weeks is a tight conceptual song cycle, Veedon Fleece is sprawling.

The album is mostly folk ballads with jazz-influenced instrumentation – all flute and heavy bass lines. But this consonance is punctuated by strange outliers: a falsetto mini opera (“Linden Arden Stole the Highlights/Who Was That Masked Man?”) and LA country rock (“Bulbs”).

Lyrically, the album shares the poetic influences of Astral Weeks, but none of the confessional realism of Blood on The Tracks or Blue. Where Dylan and Mitchell are singing explicitly about burned-out relationships, Morrison is using songwriting to escape from his – both physically to Ireland, and psychologically as he retreats into literature and mythology:

Fair play to you

Killarney’s lakes are so blue

And the architecture I'm taking in with my mind

So fineTell me of Poe

Oscar Wilde and Thoreau

This escapism is most evident on “You Don’t Pull No Punches but You Don’t Push the River”.

It’s said that in Van’s greatest songs, James Brown and John Donne are trapped in a boxing ring. Sometimes, the soul singer is victorious, other times the metaphysical poet. In “You Don’t Pull No Punches”, it’s a tie.

The song finds Van escaping from the long hangover of the 1970s – from divorce, fame and Nixon’s America – to rural Ireland, poetry and the ancient quest for the pseudo-mythical Veedon Fleece:

We’re going out in the west, down to the beaches

And the Sisters of Mercy behind the sun,

And William Blake and the Sisters of Mercy

Looking for the Veedon Fleece

In “Streets of Arklow”, Van again takes sanctuary in poetry and rural Ireland:

And as we walked through the streets of Arklow

Oh, the color of the day wore on

And our heads were filled with poetry

In the morning a-comin’ on to dawn

It’s been said that “Streets of Arklow” sounds like Motown played with Irish folk instruments. Like the rest of the album, you can listen to it with your eyes shut and be transported to a new plane – far away from day-to-day life.

It’s worth noting the state of Ireland in 1973. Civil war had engulfed Van’s native Belfast since he last visited in 1967, with ‘The Troubles’ igniting after Bloody Sunday in 1972. Van didn’t visit his home in the north when he returned.

It’s extra notable, then, that in Veedon Fleece Van is retreating to an Ireland of the ancient past. Leaving behind not only his failed marriage and the broken dream of the 1960s, but the peaceful home he left before “Brown Eyed Girl”, now under barbed wire and gunfire.

This context gives Veedon Fleece its depth of experience and feeling – real maturity, not ‘hippie’ maturity. It’s more than mere mood music: Veedon Fleece provides an escape hatch for us all. As it did for Van.

Love this review. TY.

Streets of Arklow is magical, and shows a clear line to his much later collaboration with major traditional group The Chieftains. Interestingly, Arklow is an ordinary town in Wicklow, south of Dublin, totally prosaic, but he infused it with wonder. He plays by his own rules, 100%. Amazing body of work over 60 years.